Japanese

Instruments

Koto

Of Chinese origin, the koto is table

zither 2 meters in length. It came to Japan during the Nara Period (553-794).

It is one of the few musical instruments to be typically of Chinese origin.

The other Chinese instruments that came to Japan originated in Central

Asia. In China, we find two types of table zither: one with and one without

bridges. The koto is derived from the former instrument. Originally, the

Japanese word "koto" referred to all plucked instruments. Later

on, the name came to designate the table zither. During the Nara period,

there existed two table zitehrs in Japan: the gaku-so, with 12

or 13 strings, and the wagon with 6 strings. The gaku-so

was used in the Gagaku Court music. The instrument is played with picks,

called tsume, on the thumb, the index and the middle finger.

A 2-stringed version, the nigenkin, also exists, as well as a

single stringed one, the ichigenkin. We can also find a 17-stringed

bass koto which was created at the beginning of the 20th century by the

well-known composer and koto player Michio Miyagi, as well as 20, 25 and

30-stringed versions.

Of Chinese origin, the koto is table

zither 2 meters in length. It came to Japan during the Nara Period (553-794).

It is one of the few musical instruments to be typically of Chinese origin.

The other Chinese instruments that came to Japan originated in Central

Asia. In China, we find two types of table zither: one with and one without

bridges. The koto is derived from the former instrument. Originally, the

Japanese word "koto" referred to all plucked instruments. Later

on, the name came to designate the table zither. During the Nara period,

there existed two table zitehrs in Japan: the gaku-so, with 12

or 13 strings, and the wagon with 6 strings. The gaku-so

was used in the Gagaku Court music. The instrument is played with picks,

called tsume, on the thumb, the index and the middle finger.

A 2-stringed version, the nigenkin, also exists, as well as a

single stringed one, the ichigenkin. We can also find a 17-stringed

bass koto which was created at the beginning of the 20th century by the

well-known composer and koto player Michio Miyagi, as well as 20, 25 and

30-stringed versions.

By the 17th century koto was used to accompany dances and became part

of small chamber ensembles. Previously, it was used only to accompany

the voice. A new repertoire was then created, but based on the shamisen

one (the shamisen being a 3-stringed lute covered either with snake, cat

or dog skins). In fact, the shamisen repertoire has been the source for

the repertoire of chamber music. Following these changes, the koto became

a very popular instrument.

In the 20th century, some musicians modernized the playing of the koto

based on Western music ideas. The first instigator was the composer and

koto player Michio Miyagi, a musician who became blind at the age of 6.

He died in 1957. Another musician who also modernized more the playing

of the koto was composer/player Tadao Sawai.

Shakuhachi

As

with the koto, the shakuhachi came to Japan from China with the Gagaku

Court music. At that time, it had 6 holes, similarly to today's Chinese

xiao. During the 9th century, it was removed from the Gagaku

ensemble. A century later, four Chinese monks were invited to Japan to

teach the xiao to Japanese monks. A 5-hole version was created

around the time. By the 13th century, the monks of the Buddhist Fuke sect

began using the shakuhachi as a replacement for the voice in sutra chanting.

As

with the koto, the shakuhachi came to Japan from China with the Gagaku

Court music. At that time, it had 6 holes, similarly to today's Chinese

xiao. During the 9th century, it was removed from the Gagaku

ensemble. A century later, four Chinese monks were invited to Japan to

teach the xiao to Japanese monks. A 5-hole version was created

around the time. By the 13th century, the monks of the Buddhist Fuke sect

began using the shakuhachi as a replacement for the voice in sutra chanting.

During the Edo period (1615-1868),

the shakuhachi went through major changes. Being similar to the Chinese

xiao, it was thin and long. Shakuhachi makers started to use a thicker

bamboo. At the time, the shogun was able to unify the country and establish

peace. Samourai suddently had nothing to do: they could no longer fight.

Many became ronin, masterless samourai, and joined the ranks

of roving monks called komuso. They were begging, whilst playing

on the street, wearing a straw hat which hid their identity. Disguised

as komuso, the ronin became spies, using their shakuhachi

at times as a weapon. It has been suggested that the ronin

were behind these major changes in the design and construction of the

shakuhachi.

In the 20th century, the shakuhachi went through other changes. A new

style of playing was created, greatly influenced by Western ideas. At

the end of the 1950s, a 7 hole shakuhachi was created in the hope that

it could be used to play Western music, but this did not attract the

interest of shakuhachi player, either Japanese or Westerners, and the

5 hole version remains the most popular. The 7 hole is often used to

perform folk songs. Another important change is the increasing number

of Westerners playing the shakuhachi today.

If you want to know more about these two instruments, and on the history of Japanese music, please go to the Articles page, in which you can access an article I published on the Musical Traditions Web site.

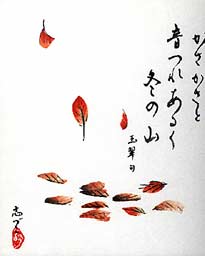

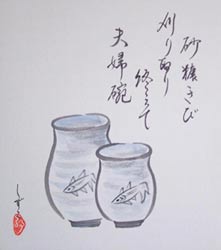

Koto

and Shakuhachi Notations

The musical notation of Japanese traditional music

is very different from Western notation, although the Japanese notation

has been slightly influenced by it in the 20th century. This tradition

notation is still used today. But we also find sometimes scores written

in Western notation.

One of the first points to mention of Japanese notation is that each instrument

has its own individual notation. The notes of a koto score are represented

by numbers indicated the strings of the instruments. The strings from

1 to 10 are represented by the Chinese number 1 to 10 (starting from the

lowest string), while 3 characters have been created for the 3 other strings.

On the hand, the notes of a shakuhachi score are represented by characters

which refers to fingerings. Few notes can be produced using different

fingerings (and different timbres); a character is used for each of these

fingerings. Moreover, scores are read from up-down, right to left, as

traditional Japanese writing.

Here are examples of Japanese notations for the koto and the shakuhachi. To these scores in regular sizes, please click on each one of them.